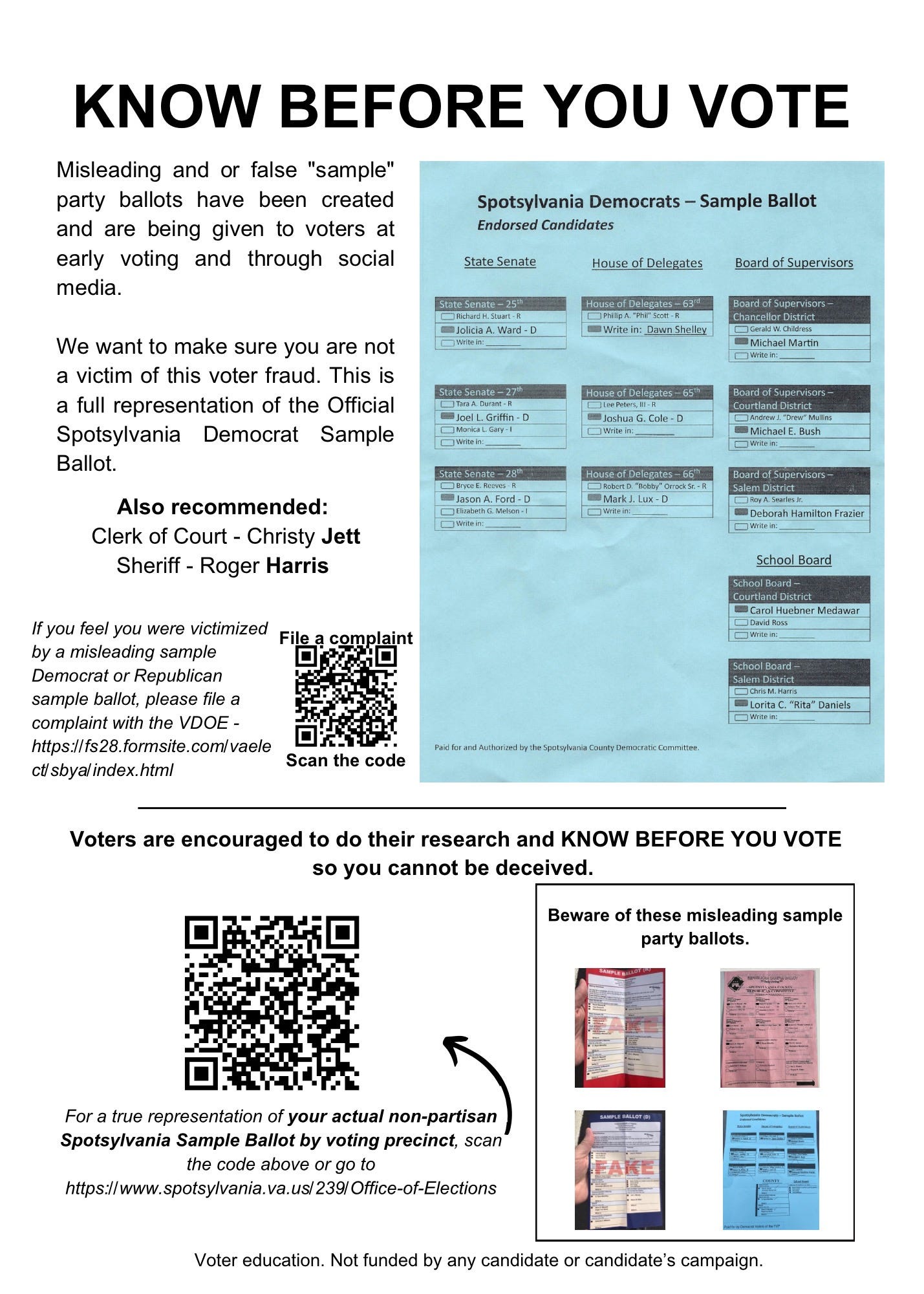

NOW came to Spotsylvania on Sunday afternoon, but abortion access wasn’t the driving issue. Rather, it was bringing awareness to voter manipulation by Nick Ignacio (candidate for Clerk of Court in Spotsylvania) and Steve Maxwell (candidate for sheriff) at the Early Voting site in Spotsylvania.

The blatant misinformation these two have been pushing is a concern not only for citizens locally, but for the health of democracy in this region moving forward.

The question that circulates among those in the county who have learned of the issue, but don’t necessarily track politics closely, is a good one. “Can’t we do something about this?”

According to Sen. Jeremy McPike, D-SD 29, this is playing out in a “difficult space.”

There appears to be no specific law in the Virginia State Code that prevents people from passing out misinformation at the polls, though a case could be made.

Unfortunately, that’s a case that would have to play out between the state Board of Elections and the court system. So while it’s possible to revise the code to address this particular concern, the election will be long past by the time that conclusion is reached.

Hence, the “difficult space” that this situation is playing out in.

Can anyone stop what’s going on?

At the center of this difficult space is Kelli Acors, the General Registrar of Spotsylvania.

The line of thinking is that she, and she alone, has the authority to put a stop to the nonsense occurring outside the Early Voting site. According to Troy Skebo of the Spotsylvania Sheriff’s Department, who was also present Sunday, Acors says the answer to that belief is “No.”

Nicole Cole, who sits on the school board in Spotsylvania County, believes Acors does. Cole points to the registrar in Henrico County, who has strictly enforced rules about signage (only at tables), and campaign staff (no more than three at a site per candidate).

Acors setting those two rules alone would greatly improve the situation in Spotsylvania right now.

This isn’t the first time this campaign season, however, that Acors has found herself embroiled in controversy. This summer, the Advance broke the story that Acors counted as valid the signatures collected on January 1, 2023, by Ignacio and Maxwell in violation of the Board of Election’s own guidelines.

Had she not counted them, as would have been correct, Ignacio and Maxwell wouldn’t have had enough signatures to be placed on the ballot.

It’s an error that she admitted to making in her interview with the Advance.

[We asked] Acors via email what her understanding of the correct date to receive signatures actually is.

Her answer to us on Tuesday?

“Post these inquires, calls and emails, yes – 1/2/year in question not the beginning of that election ‘cycle’ which is the beginning of the year.”

McPike requested a ruling from Attorney General Jason Miyares around the time we broke this story. To date, Miyares has not weighed in.

The law, in short, can’t, or won’t, fix what has been broken in Spotsylvania.

Laws and Civic Virtue

What can fix the moral rot on display in Spotsylvania is to regain our commitment to the unwritten civic virtues that have long guided our behavior, and which Ignacio and Maxwell have clearly abandoned.

These civic virtues are broad and necessary in a free society. It isn’t possible to pass enough laws to touch every single immoral action people may take. And in any case, once something is written down, then the quest begins to find the next “difficult space” where Machiavellian ideology – i.e., “So long as I win, the tactics I use are right” – can take hold.

We have been, for the better part of 200 years, a pragmatic people who have balanced law and civic virtues.

Pardon my reference to a Dead White Thinker, but Ralph Waldo Emerson explicitly outlined this distinction in 1838, when he delivered the “Divinity School Address” at Harvard.

Aimed at criticizing Christianity’s rigid laws and requirements to be involved in a religious community, Emerson instead charted a path toward a more-open type of spirituality. One that has each person getting in touch with the divine inside of themselves.

If that seems a far stretch from the political reality we’re living in, consider what Emerson writes:

The sentiment of virtue is a reverence and delight in the presence of certain divine laws. It perceives that this homely game of life we play, covers, under what seem foolish details, principles that astonish. … These laws refuse to be adequately stated. They will not be written out on paper, or spoken by the tongue. They elude our persevering thought; yet we read them hourly in each other’s faces, in each other’s actions, in our own remorse.

(Emphasis added.)

We might summarize what Emerson captured this way. We don’t need laws to know that what is happening in Spotsylvania is wrong. We see it in the faces of the perpetrators, who cling to the ambiguities in the written law to justify immoral behavior.

Candidates should “win a vote honestly” by educating voters and helping them know who to support, McPike told the Advance, “not trick voters.”

We concur. And it shouldn’t take a law to put a stop to what is happening in Spotsylvania. The underlying moral laws of moral action and character, upon which our laws exist, should be more than enough.

If Spotsylvania is to regain the integrity it has ceded to the Maxwells and Ignacios of the county, leaders and people of good faith need to enforce the civic virtues by insisting the inaccurate documents not be allowed at the site.

The question is, do we still have enough of an attachment to the virtues of democracy to so act.

Emerson has shown the way. Let us follow.