In my previous life as a book reviewer for The Free Lance-Star, the Book Page rarely reviewed books more than year old. On the rare occasions when my editors would relent to my pleas, it would be a book of local relevance or one that was particularly timely, like Albert Camus’ The Plague during Covid.

The Fredericksburg Advance still aims to review recent titles, but is also offering an opportunity to review books of local and timely relevance such as any of the titles that have been banned from Spotsylvania County schools.

And that brings us The Bluest Eye.

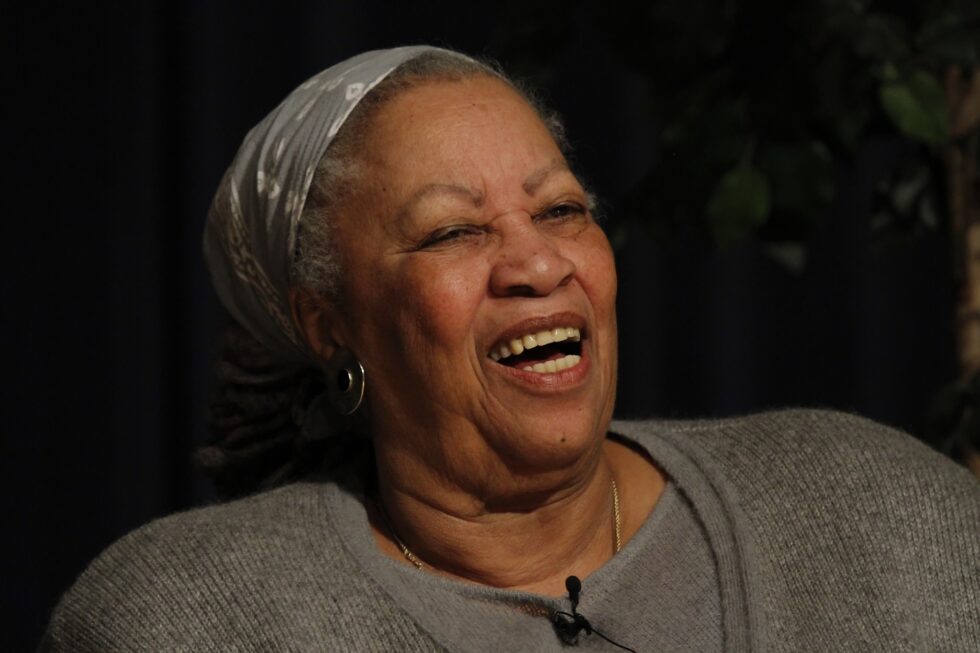

Toni Morrison’s debut novel is one of those banned books and regularly appears on the conservative book hit-list of titles to ban.

The argument against The Bluest Eye is generally couched in its portrayal of incest and child sexual assault, but it probably also has something to do with Toni Morrison being a black author who writes elegantly and unflinchingly of the black experience. What I find most shocking about The Bluest Eye, however, is that it was published in 1970, the same year I was born.

How did it take 53 years for this novel to offend parents and school boards? The unfortunate and obvious answer is that some parents and some school boards are viewing their roles in education much differently than they did in the past 50 years. The literature embraced by prior generations be damned. These are the preachers of our collective morality and the protectors of the world’s suburban children. And when they are at long last able to breach the walls of our public schools, the library collections, selected by learned and careful professionals, are their old zebra trailing the pack–the easiest prey.

The story of The Bluest Eye is the story of Pecola, a black teenage girl in Ohio who most agree might be the ugliest child in the history of children. Pecola senses her ugliness and the world’s contempt because of her looks and believes that if she simply were able to have blue eyes she would have a chance in the world.

Morrison writes Pecola’s story and history through the eyes of family and friends. The paths that lead to a young girl who sees herself as worthless are not easy or straight. A lot of the world’s ills and hate have to engulf lives that were lived generations before Pecola exists. These are hard people with hardscrabble lives, and little room for the American Dream.

The making of children has historically required having sex, and Morrison portrays the act of sex in The Bluest Eye. Read the passages as standalone in any school board meeting and they will certainly elicit the anticipated gasps from outraged citizens who have been subjected to the profane while at a meeting to simply ask about a bus route change.

Within the context of the book, however, these passages are important and show that sex can be bestial rather than beautiful, and can have consequences that affect a life forever. These are important elements of being a teenager when faced with the daunting prospect of fast-approaching adulthood.

What a reader also gets in Pecola’s story is poetry. Based upon The Bluest Eye and subsequent titles, including Beloved (also frequently banned), Morrison became an American literary icon and deservedly so. Her prose can be breathtaking and return a reader to their past as in this passage where a young boy named Cholly, later to become Pecola’s father, has his first flirtatious encounter with a girl.

The object of the walk was a wild vineyard where the muscadine grew. Too new, too tight to have much sugar, they were eaten anyway. None of them wanted—not then—the grape’s easy relinquishing of all its dark juice. The restraint, the holding off, the promise of sweetness that had yet to unfold, excited them more than full ripeness would have done. At last their teeth were on edge, and the boys diverted themselves by pelting the girls with grapes. Their slim black boy wrists made G clefs in the air as they executed the tosses.

The innocence portrayed in this passage quickly dissolves and, for Cholly, becomes a memory that haunts him for the remainder of his life. From this foundational moment, Cholly’s life unravels and we understand that Pecola had no chance in this world, but in her dream of blue eyes there existed a shadow of hope.

I can throw any number of platitudes at The Bluest Eye but they would simply be the same adjectives others have used over the last half century to describe this magnificent book.

What I believe to be more important in this present climate is that to deny both students and teachers the opportunity to read Morrison and Pecola’s story is a disservice to their ability to educate and be educated.

To pull a book of such import from library shelves is short-sighted and harmful. As with all books that my children have wanted to read (and oh how I wish they read more), if there is a question on the book then I will read it myself and decide if it is suitable for my children.

I did not read The Bluest Eye with any notion that my opinion of the book and its substance should govern an entire county’s school system. That would exhibit both a degree of hubris and ignorance that would embarrass me and should embarrass others who think otherwise.

I am not black and have never wished for blue eyes, but I do know when I have read a book of staggering majesty and would never deny others their opportunity to experience such significance.

Drew Gallagher is a freelance writer residing in Fredericksburg, Virginia. He is the second most prolific book reviewer and first video book reviewer in the 136-year history of the Free Lance-Star Newspaper. You can find some of his video book reviews at Fredericksburg.com.

Image credit: “Toni Morrison Lecture_012” by West Point – The U.S. Military Academy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.