by Adele Uphaus

MANAGING EDITOR AND CORRESPONDENT

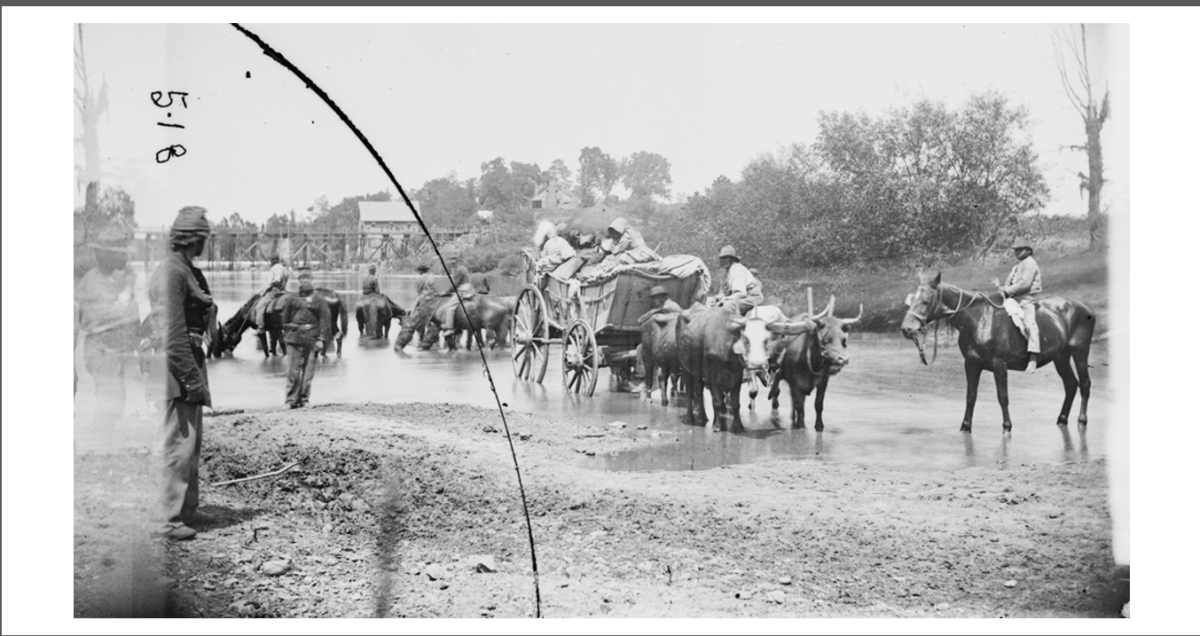

In the Fredericksburg area today, we’re accustomed to crossing the Rappahannock River with ease, often multiple times a day, to get to work, or to an appointment, or to run an errand.

Two hundred years ago, a young, enslaved man named James attempted to cross the river in order to save his own life—and he was not successful.

“I think about James every time I cross the Chatham Bridge,” said Gaila Sims, curator of African American history and special projects at the Fredericksburg Area Museum.

On Saturday, Sims—along with Beth Parnicza, ranger at the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, and Alexa McNeil, FAM’s social media manager—conducted guests on a preview of a new trolley tour titled “Sparking Freedom: Enslaved Resistance in Fredericksburg and Stafford, Virginia.”

James’s story is one of those shared on the tour, and it is “one of the hardest stories of the entire tour,” Parnicza said.

In January of 1805, James was one of a number of enslaved workers who participated in an uprising at Chatham, the Georgian manor house built in 1771—by enslaved people—and owned by the Fitzhugh family.

The only sources of information about the 1805 Chatham uprising, Parnicza said, are newspaper accounts written by white men, so it’s not clear if it was preplanned or not.

It happened during the Christmas holidays, the only time of the year when enslaved men and women were traditionally given a break from their labors and had space to visit friends and family on neighboring plantations, tend to their own homes, and celebrate.

That year, Chatham’s new overseer, a man named Mr. Stark, attempted to call the enslaved workers back from their holiday early. The result was that an unknown number of them “rose in a body and refused compliance,” according to one newspaper account.

Stark was twice captured and beaten up, but he managed to escape and returned with “a large armed party.” In the ensuing violence, one of the enslaved men who participated in the uprising—Phil—was shot and killed.

Another, James, attempted to flee across the frozen Rappahannock River, but he fell through the ice and drowned.

A third, Abram, was later tried and executed, and two others, Robin and Cupid, were transported out of Virginia and their fates are unknown.

Chatham’s owner, William Fitzhugh, received at least $1,000 in remuneration from the state of Virginia for the loss of his “property.”

The story of the Chatham uprising is a brutal example of an act of resistance that was not successful and of the violence the slave-owning society was prepared to enact as punishment—and it underscores the courage of enslaved men and women who continued to resist all the way through the Civil War.

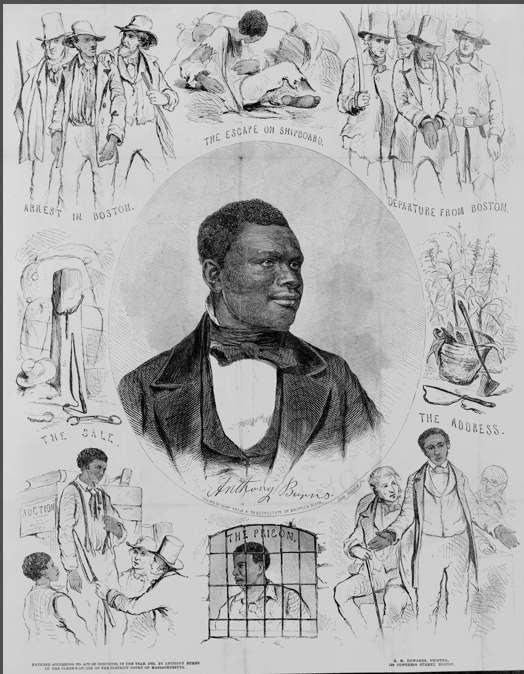

In addition to Chatham, the tour involves nine other stops at sites in Falmouth and downtown Fredericksburg. Participants will hear stories of enslaved people who used their “light skin” to pass as white or raise money to buy their own freedom and that of their families, who faked illnesses to ensure that they wouldn’t be sold at auction, who escaped in boxes and in ship compartments or by crossing the river.

Participants will also hear about possibly less dramatic but no less courageous acts of resistance—performing a job badly, gathering in public, going to church, keeping up African traditions, and simply “finding joy,” Parnicza said.

FAM received a grant from the National Parks Foundation’s ParkVentures program to put together “Sparking Freedom,” which was developed along with the National Park Service and Discover Stafford.

“Sparking Freedom” will be offered as a free public tour throughout 2024. A video of the tour filmed by James Rapelyea will soon be available at the FAM website.