Supervisors voted in 2021 to remove the monument from in front of the county courthouse.

A monument originally dedicated in 1869 to the men of King George County who fought for the Confederacy, which was moved September 10, 2022, from its long-time location in front of the county courthouse, was re-dedicated at its new location in Historyland Memorial Park on U.S. 301 in a ceremony on July 6.

There’s quite a back story to the monument.

Following the Civil War, the federal government took care of graves and monuments for Union soldiers and sailors only, until subsequent legislation in the 20th century in the spirit of reconciliation recognized Confederate veterans as U.S. veterans, also. Today the U.S. government will pay for headstones for Confederate graves, for example.

However, in the immediate aftermath of the war, it was up to the Southern states to provide graves and monuments for their soldiers. This was the impetus for the formation of numerous “ladies memorial associations” throughout the South.

Fredericksburg’s, formed in 1866, is one of the oldest, and is still active today.

The Ladies Memorial Association of King George County was formed in 1867. (It does not appear to be active currently.)

The 24-foot granite obelisk funded by the ladies was initially placed at the county courthouse in 1869. Subsequent relocations of the courthouse, usually due to road construction, caused the monument to be moved in turn, most recently in 1976.

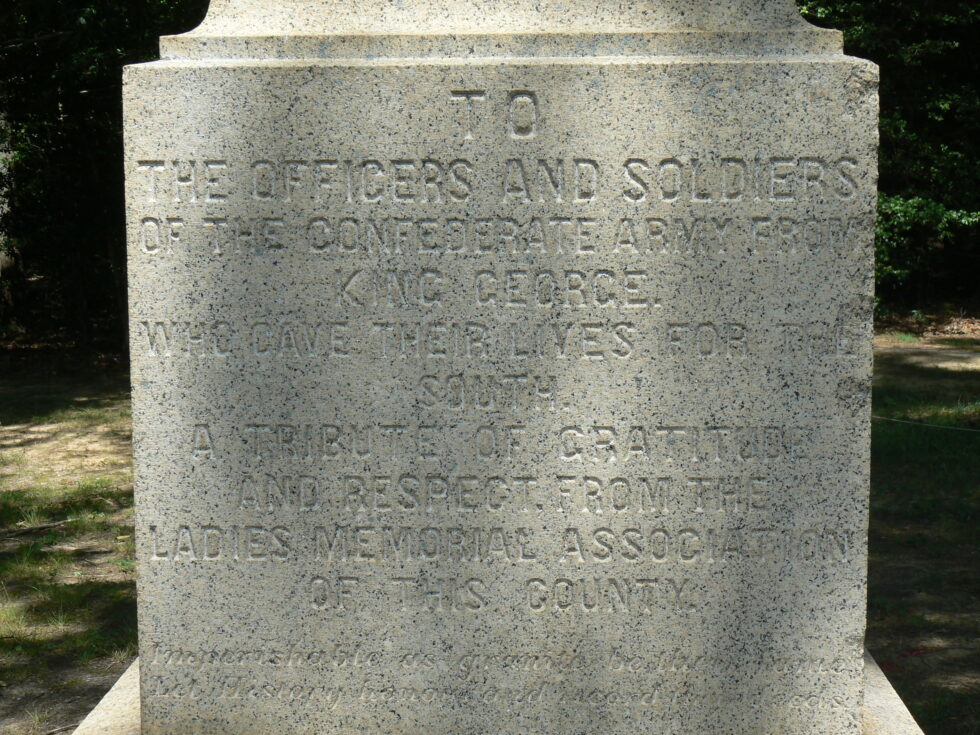

The inscription at the top of the side now facing Rt. 301 reads:

To the officers and soldiers of the Confederate Army from

King George. Who gave their lives for the South.

A tribute of gratitude and respect. From the

Ladies Memorial Association of this County.

Imperishable as granite be their fame.

Let history honour and record their deeds.

There are 282 names inscribed on the monument, according to a document written in 1965 by Ellamae H. Clare, a deputy clerk at the county court clerk’s office.

Time has taken a toll on the clarity of the names, and a small bronze marker in front of the monument refers the curious to the county clerk’s office for a complete list, which this reporter obtained.

Of the 282 names on the monument, 96 died in the war, according to a book compiled in 2012 by Jean Moore Graham and Elizabeth Nuckols Lee, King George County Confederate Monument: A Glimpse into the Lives of Those Who Served.

The book also includes the names of other county Confederate veterans whose names were not included on the monument for various reasons. It has brief biographies of all the county’s Confederate soldiers.

Some of the names on the monument lack marked graves, according to Gloria Sharp of the King George County Historical Society, so the only marker for them is their presence on the monument.

The momentum to move the monument came in the wake of the May 2020 murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, which led to much public re-thinking across the nation about Confederate-themed monuments.

King George resident David Jones, whose ancestor was a Confederate soldier, asked the county Board of Supervisors in July 2020 to remove the monument from the grounds of the courthouse.

The local chapter of the NAACP supported this request. Others spoke in opposition to the idea, saying it was disrespectful to the memory of the soldiers from the county who answered the call to fight in the war, or an attempt to erase history.

The Board voted to move the monument on November 23, 2021, in a split three-to-two vote.

Moving the monument cost $38,000, and was paid for privately. The owner of Historyland Memorial Park donated the site at the back of the cemetery under a grove of trees.

The ceremony was hosted by the Matthew Fontaine Maury Camp 1722 Sons of Confederate Veterans group from Fredericksburg.

The ceremony included the laying of wreaths, release of doves, rifle and artillery salutes, a brief speech on the Confederate soldier’s point of view, a bugler playing Taps, and local priest Father Francis M. de Rosa providing the invocation and closing prayers. Camp commander Roy Perry read a poem he wrote, ending with “King George, these are your sons.”

In addition to the 15 or so Camp 1722 members present, about 20 spectators attended the event.

By Scott Boyd

GUEST COMMENTATOR