by Adele Uphaus

MANAGING EDITOR AND CORRESPONDENT

Anna Pomaska has written and illustrated more than 100 books for children in the past 45 years—possibly more than beloved children’s authors Maurice Sendak and Dr. Seuss.

Her art was so prevalent in the childhood of those who grew up in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s that it seemed to be just part of the universe, said Paul Cymrot, owner of downtown’s Riverby Books.

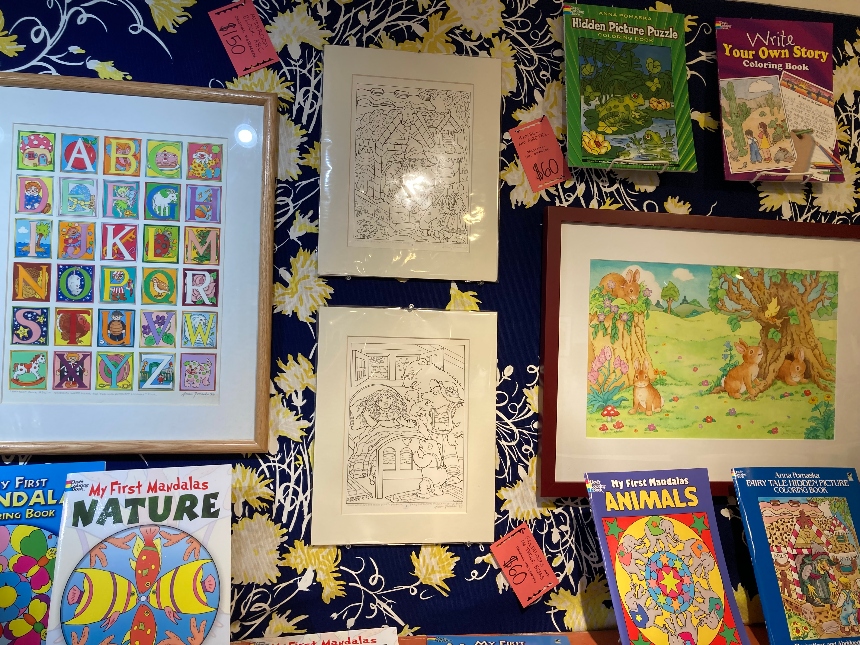

Her name was even included as part of the titles of the activity books she wrote and illustrated for Dover Publications—“Anna Pomaska’s Create Your Own Pictures,” “Anna Pomaska’s Fairy Tale Hidden Picture Coloring Book”—yet few people outside of the teaching profession know her name.

“[These books] were sort of everywhere,” Cymrot said. “This is what was around. I feel like they were in everybody’s houses. It never occurred to me that someone had made these. They sort of existed in the world.”

But someone did make them, and it turns out that Cymrot knew her. Pomaska and her husband, who have lived in Urbanna, Virginia, since 2007, are longtime friends of Cymrot’s in-laws.

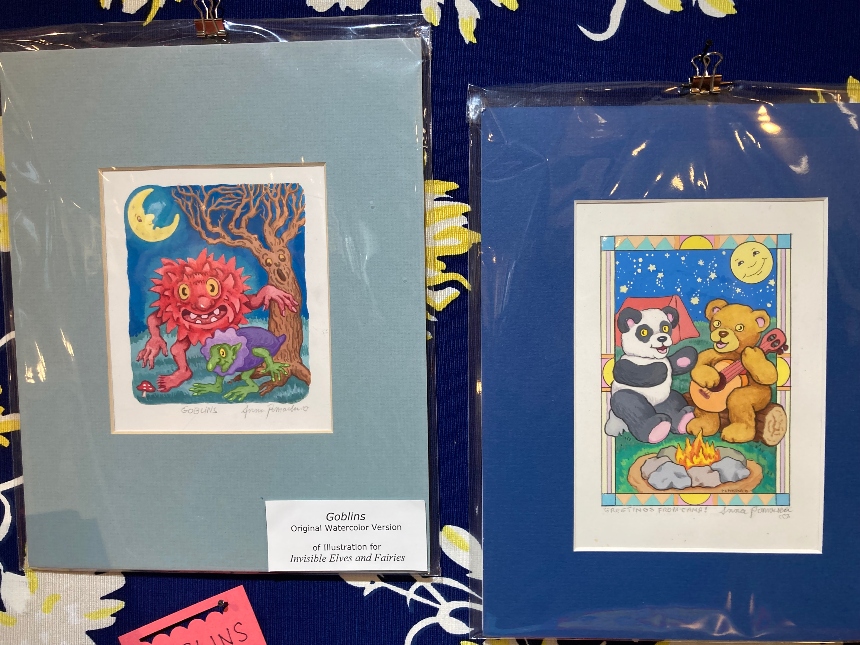

Riverby Books is hosting an exhibit of 50 of Pomaska’s works, including original prints of the artwork from her coloring and activity books.

Pomaska was born in Scotland and recalls “always drawing” as a child. She was inspired by the popular cartoon character Rupert the Bear, who debuted in 1920.

Pomaska said the Rupert stories, with their nature-based settings, were soothing to her, especially after her family emigrated to urban Buffalo, New York.

She studied fine art at the Pratt Institute in New York City and was part of the city’s “high art” scene, but she was always also drawn to “simpler” forms of art, like coloring books.

“I find that they’re very empowering,” she said. “When there are maybe things you can’t quite control, there is something [empowering] about saying, ‘I can actually complete this.’”

In 1975, Dover’s founder Hayward Cirker hired Pomaska to create the art for the publishing company’s line of activity and coloring books.

Cymrot said that in researching the show, he has attempted to figure out who came up with the concept of dot-to-dot, hidden picture, spot-the-difference or “what’s wrong with this picture” activity books, or whether there were other artists producing them at that time.

“[Pomaska] claims no credit for spot-the-difference or hidden letters or anything like that, even though I can’t find the creator,” Cymrot said.

The only concept she will claim some credit for is a certain subset of dot-to-dot in which children illustrate a story as they work through the book—though she won’t say she created it, just that it’s “a little unique.”

“I also tried to make it so the children couldn’t know what they were going to come up with [until they connected all the dots],” Pomaska said. “I found that now they’re saying that’s so unique, but for me, that was always the point. I wanted very much to have kids not know what [the final image] was going to be.”

For Cymrot, this speaks to why Pomaska’s books were—and still are—so impactful.

“Teachers have talked to us about the sense of accomplishment these activity books instill in young children, and about the slow, cumulative sense of confidence that comes with achievement,” he wrote in a Facebook post about Pomaska. “If you can solve these puzzles, you can solve other puzzles, after all. We can’t help but think about Mr. Rogers and Big Bird, icons of early childhood for generations of children. They spoke directly to kids. There was no subtext, no hidden meaning, no ironic twist to anything they said.”

“We could talk about how a dot-to-dot teaches a child to follow instructions, to take things one step at a time, to break down big projects into manageable steps. Anna would probably prefer to say that they are soothing and fun, and that watching the picture come into focus is exciting.”

Today, crossword puzzles, jigsaw puzzles, word searches, and games like Wordle are hugely popular, as are adult coloring books.

“What are these things tapping into if not that same sense of accomplishment that Anna’s activity books instilled?” Cymrot wrote. “Clearly, we never stop seeking out puzzles we can (usually) figure out.”

Pomaska estimates that she probably wrote and illustrated more than 150 titles for the company. Many of them are still in print, but she was only paid once for her work and doesn’t receive any royalties from their continued publication and sale.

All of Pomaska’s original artwork at Riverby is for sale—if it hasn’t already been sold—and copies of her activity books are also for sale. The exhibit will be up for the next two months at 805 Caroline Street, Fredericksburg.