Five new wayside panels add to the story already told on the downtown portion of the Trail.

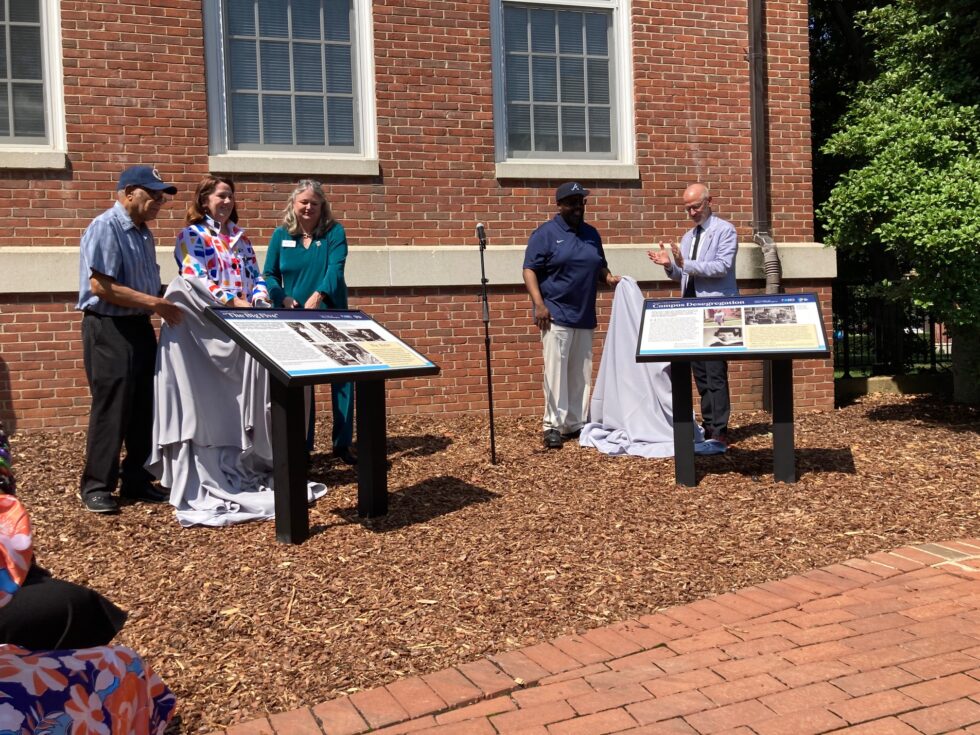

Almost four years to the day after an email exchange that initiated work on the Fredericksburg Civil Rights Trail, city and University of Mary Washington leaders unveiled five wayside panels that complete the trail.

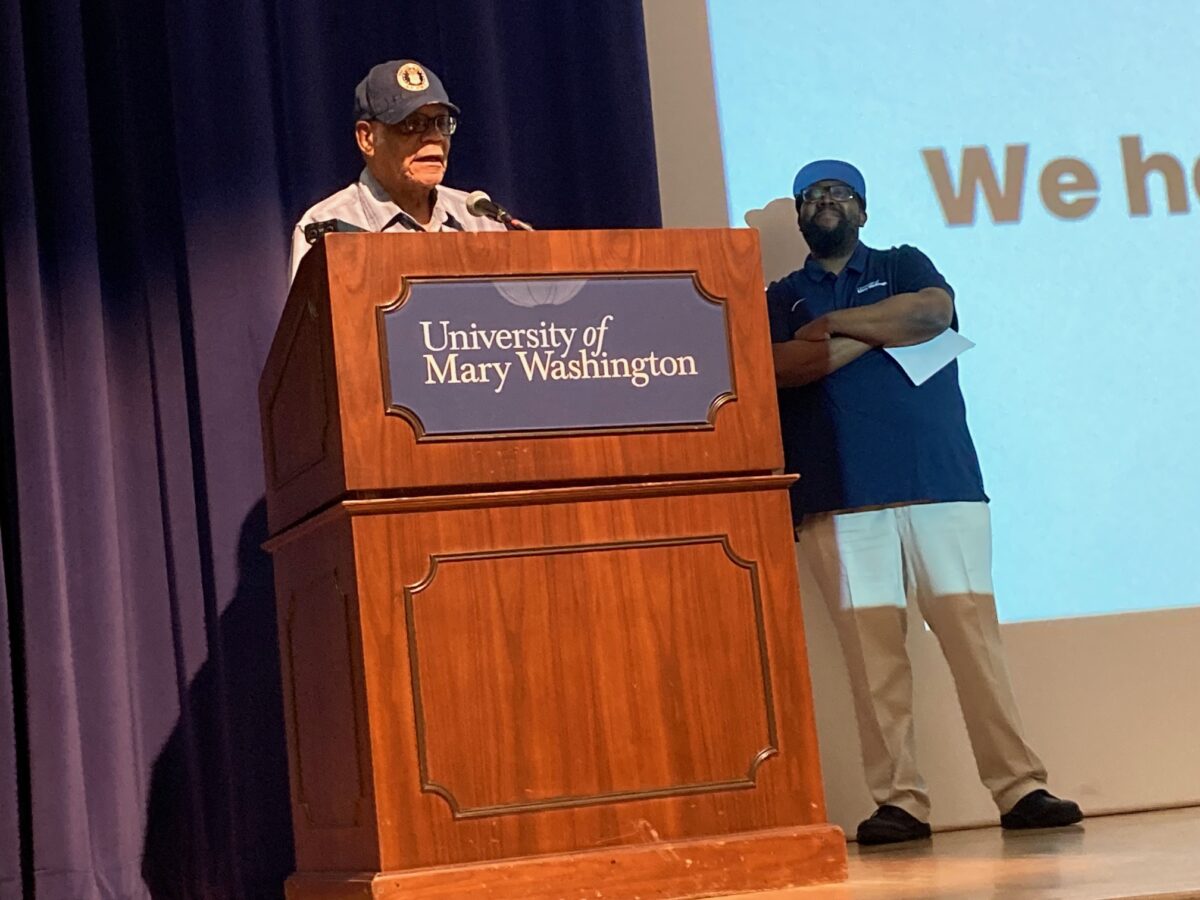

“This is the last unveiling we will have,” said Chris Williams, assistant director of UMW’s James Farmer Multicultural Center.

He described receiving an email on July 17, 2020, from Victoria Matthews, tourism sales manager for the City of Fredericksburg, suggesting that they start work on a local civil rights trail, an idea they’d discussed for an hour at a holiday party the previous December.

The first section of the Civil Rights Trail, a 2.6-mile tour with stops at 12 sites in downtown Fredericksburg, was unveiled in February 2023, along with three new wayside panels, one history panel, and two state markers to expand on the story.

This February, the Fredericksburg Trail was added to the U.S. Civil Rights Trail, “catapulting [the city] into the national spotlight,” Mayor Kerry Devine said.

On Tuesday morning, Devine, Williams, Matthews and UMW president Troy Paino unveiled five more wayside panels that make up the second section of the trail on the university campus.

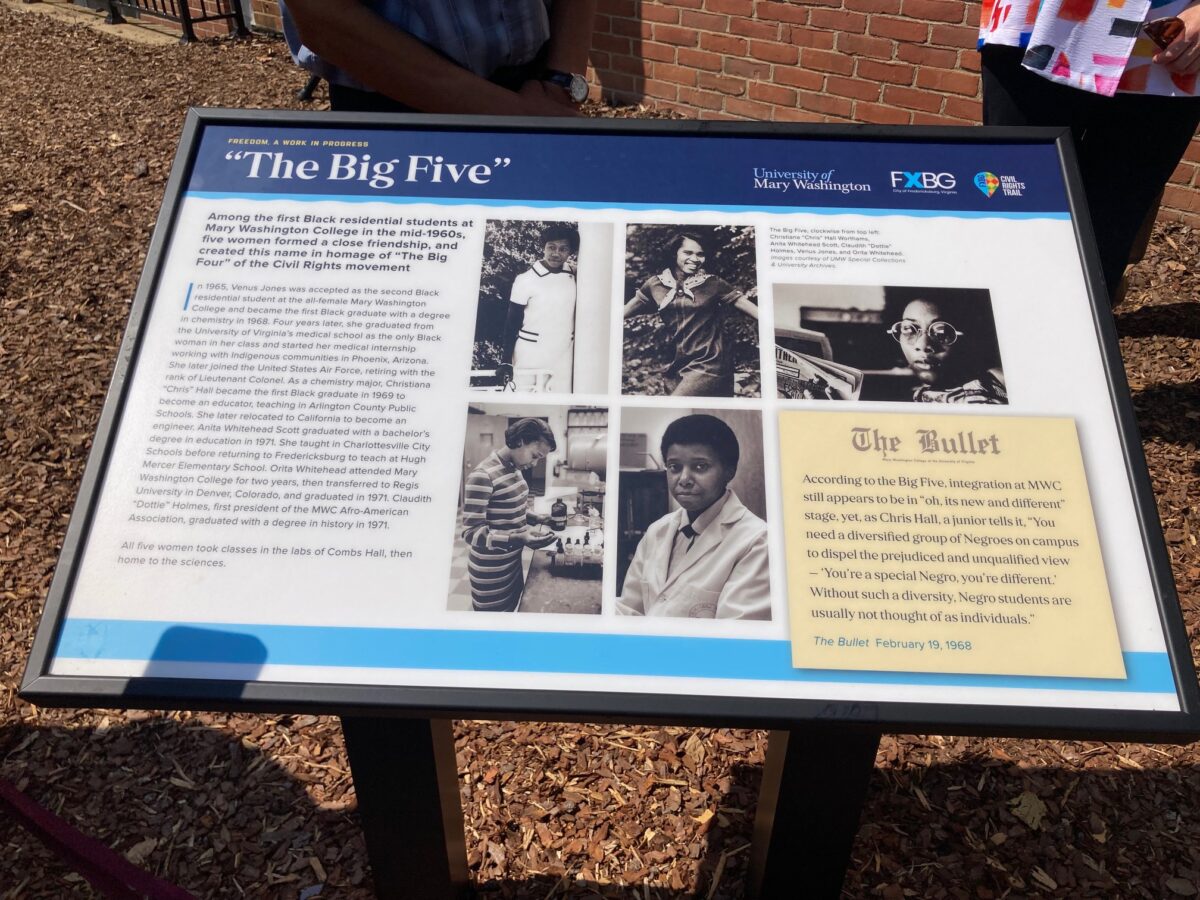

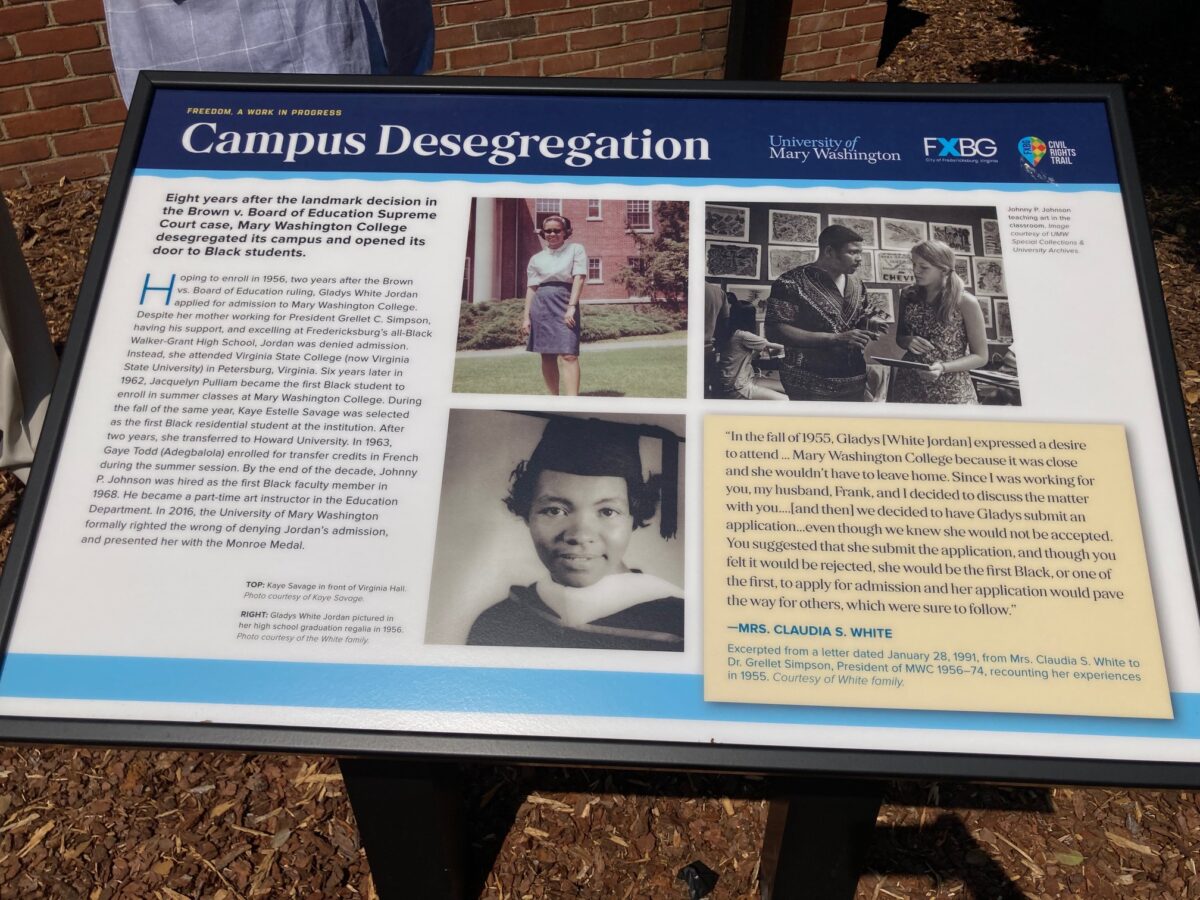

Two panels in front of Combs Hall tell the stories of the Black students who desegregated the university in the 1960s as well as the “Big Five”— the first Black residential students.

In the audience at Tuesday’s ceremony in Dodd Auditorium were three younger brothers of Gladys White Jordan, who in 1956 became the first Black female to apply to what was then Mary Washington College, the women’s college of the University of Virginia.

“Our mother worked at Brompton [the home of the UMW presidents] for [then-president Grellet Simpson],” Frank White said. “He told her, ‘You should have Gladys apply as a commuter student.’”

White said Simpson told their mother that if it was up to him, Gladys would be admitted, but it wasn’t up to him—it was up to the UVA admissions staff.

Gladys did apply. While the application didn’t ask her to identify her race, it did ask what high school she’d graduated from, and Gladys put down “Walker-Grant High School,” which was the segregated city public school for Black students.

“It didn’t take a rocket scientist to read that and realize who you are,” White said. “They turned her down.”

Gladys White Jordan went on to earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Virginia State College and become a beloved teacher at Ralph Bunche High School in King George County.

It wasn’t until 1962 that the first Black student, Jacquelyn Pulliam, took summer classes at Mary Washington and later that fall, Kaye Estelle Savage enrolled as the first Black residential student.

Savage was present at the unveiling of the marker telling hers and Jordan’s stories.

The other three panels unveiled Tuesday describe the achievements and legacy of James Farmer, a noted Civil Rights leader and one of the original Freedom Riders who later taught at UMW; discuss the role of the James Farmer Multicultural Center; and talk about student advocacy for civil rights.

UMW students in the past several years have worked with Williams, geography professor Steve Hanna, and historic preservation professor Christine Henry to research the stories that the markers now tell and build the physical and online map of the Civil Rights Trail.

Paino said this kind of learning opportunity is “on brand” for the university and that the stories the trail tells can serve as a much-needed beacon of hope for the generation that’s now coming up.

“We feel stuck as a country,” he said. “We have to remind ourselves that this is a point in time and that we can do [what was achieved during the Civil Rights Era] again.”

Hanna said that as a “human geographer,” his work focuses on what stories from the past are made present in our physical landscape, and what stories we choose to keep private.

“As I’ve heard [Vice Mayor] Chuck Frye say many times, ‘Black History is American History,’” Hanna said. “It’s vital that this be cemented in our landscape.”

“We have to make these stories as visible as fireworks on the Fourth of July,” he said.

By Adele Uphaus

MANAGING EDITOR & CORRESPONDENT

Email Adele