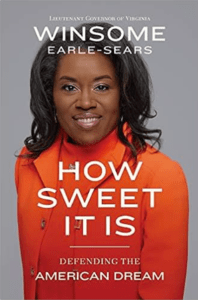

Independent voters jaded over actions on both sides of the aisle should find Jamaican born Lieutenant Governor Winsome Earle-Sears’ life experiences not just remarkable, but politically contentious.

Using a religious simile stating she wanted to “do a Moses” in her first run for office, defeating a 20-year Democratic incumbent, perhaps summarizes her life. Theological beliefs notwithstanding, Sears can be called a Christian nationalist in the tradition of the Founding Fathers, and to her such a label is a badge of honor.

What follows is a comfortable 238-page read of a remarkable life dealing with personal challenges, how her faith has shaped her character, and her family’s search for the American dream. Sears’ book is a first-person history coping with ethnic pride, validating divine providence, and political sense and sensibility in light of the tragedy of losing a daughter and grandchildren because of mental health issues.

Those who know her acknowledge Sears’ compassionate but results-oriented persona as former director of a women’s homeless shelter in Chesapeake, stating “I thrive in ordering chaos.”

As today’s minority community still reels from COVID, with financials still compromising the working class, not all will respect her Jamaican family history with frank consternations over the socialist and Marxist schemes of Jamaica’s extreme leftist Michael Manely in 1972.

Earle-Sears references V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River validating socialism’s shortcomings and to emphasize how the black community has not necessarily advanced with liberalism.

Yet aside from faith and family, it was a stint in the Marine Corps as an electrician which in many ways continues to shape her life.

A lady with tremendous fashion sense, she nevertheless showed comfort posing with an AR15 on the campaign trail for Lieutenant Governor. Once a Marine, always a Marine, as the saying goes.

Credit the Corps for advancing her patriotism, but not the totality of her work ethic. With pride she boasts of her grandfather who instilled “There is no such thing as ‘can’t’ in our family.”

Demonstrably, her sense of industry was engrained early from a mother working as a line supervisor making tin containers in Jamaica, and a father arriving in the United States with $1.75 in his pocket immediately seeking a responsible occupation.

Winsome shares her pride and fascination with other family icons such as Aunt Babs, the “thoroughly modern 1970’s woman” who was an OR nurse.

Impressive is her understanding of the slave narrative and the three things vital if one’s family came from slavery. Number one, the desire for freedom. Number two, to be reunited with one’s family, and number three, the need for education. Winsome’s statement “Slaves understood that education was the road out of poverty and powerlessness,” remains profound.

Winsome’s repeated references concerning her prayer life and signals from God can be intimidating to those of us who refuse to accept deity or acknowledge communication from one’s creator. Yet it is fascinating to read about the behind-the-scenes actions as conservatives channeled parental rights concerns over Critical Race Theory (CRT) which proved to be the Achilles heel of liberals during the the gubernatorial election.

One item notably missing in Winsome’s memoirs was not just her story about settling in as Virginia’s Lieutenant Governor, but what her future may hold. Certainly, Virginia Congresswoman Abigail Spanberger will no doubt read this book cover to cover in an effort to know how to engage a woman who also has gubernatorial ambitions.

Win or lose, no doubt this will be in Winsome’s next publication.

Daniel Cortez of Stafford is a long-time writer/broadcaster, a Presidential Appointee and serves as the volunteer co-chairman of the Latinos for Youngkin Coalition